Personality Theory, the Brain and the Personal Unconscious

Early Development, Attractors and the Limbic Personality

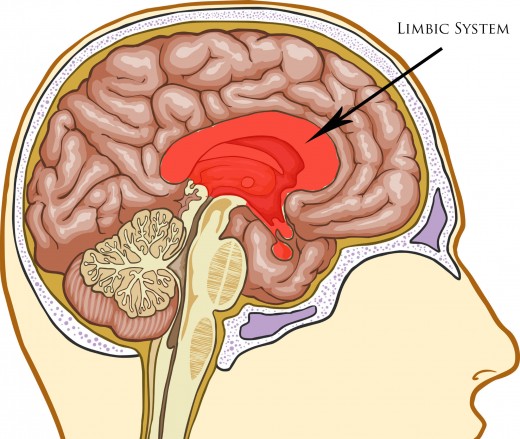

Because brain plasticity—and its capacity to be molded by experience—is so dynamic in the first two or three years of life, experiences during this period of time exert pervasive influence on the developing personality (Schore, 1994, p. 3). The predominant brain structures in play at this time include the right hemisphere (Geschwind & Galaburda, 1987) and limbic system (Joseph, 1982), between which at this time extensive neural circuitry already exists (Tucker, 1981, 1992). Of these structures, the amygdale, situated on either side of the limbic system within the center of the brain, share a fast track to the brain’s sensory relay station—the thalamus (Goleman, 1995, p. 18). As a result, the amygdale rapidly communicate negative and potentially threatening information more quickly than positive information (Jiang & He, 2006; Vaish, Grossmann, & Woodward, 2008; Yang, Zald, & Blake, 2007).

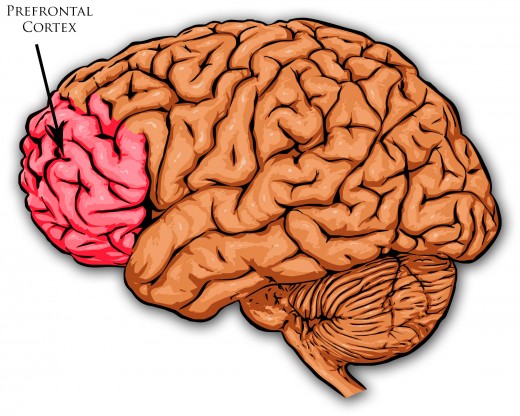

Based on additional evidence for prevalent limbic influence on the personality (Baumeister, et al, 2001; Peeters & Czapinski, 1990), Waller (2007) theorizes that unmet emotional needs in early development generate negative emotional experiences, which then leave their indelible imprint upon the limbic system (p.80). These imprints act as attractors (a term used in nonlinear dynamics to denote systemic patterns toward which physical systems tend to evolve), around which the chaotic energy of the limbic system forms (p. 50), thereby deeply embedding the energetic pattern of those negative experiences into the limbic system’s neural circuitry (Schore, 2003b, p. 4). Waller (2007) further theorizes that, because the limbic system is almost fully wired by age five (p. 35), many years before the higher order cognitive processes of the frontal and prefrontal lobes come online, and because limbic-mediated emotion has been shown to be involved in all intentional behavior (Freeman, 2000), these imprints play a large role in motivation throughout life (Waller, 2007, p. 50).

Waller (2007) views the personality as the result of unconscious identification with both inherited traits and environmental conditioning (p. 140), both of which deeply impact neural development (Mundkur, 2005; Sarnot & Menkes, 2000). When such conditioning is deeply identified with, it solidifies the experience of a solid self and personality (Waller, 2007, p. 140). In the early stages of development, the fledgling limbic system becomes imprinted with the energy pattern left by experiences of both met and unmet emotional needs (p. 80), giving rise to reactive and goal-oriented motifs that are eventually and mistakenly identified as the self (p. 140).

Certain Eastern spiritual traditions have viewed the formation of the personality in much the same way. The Tamil Siddha tradition, for example, sees the developing personality as an amalgamation of culturally conditioned neurological responses being unconsciously animated by the life force (Sadleir, 2003, p. 12). Also known as prana (Krishna, 1997, p. 68), this life force is a somewhat superficial aspect of a deeper creative power, referred to in yogic traditions as the kundalini-shakti (Goswami, 2006, p. 237), which unconsciously animates bodily processes, giving rise to the mental and emotional content of the phenomenal mind (Muktananda, 1978, p. 48), with which an aspect of the underlying consciousness identifies (Sadleir, 2003, p. 12).

The aforementioned limbic conditioning is theorized by Waller (2007) to give rise to a dialogical self, the ever-active and automatic self-talk activated by limbic attachments and aversions (p. 65). By consistently recruiting other brain areas into its employ, Waller speculates that this limbic-generated, dialogical self regularly hijacks the frontal lobes and thereby significantly biases perception (p. 50). Identification, in his view, is seen as taking place by way of the prefrontal function mistakenly identifying the dialogical self as the locus of the self, since the prefrontal lobes do not fully develop until long after the voice of the dialogical self has become active (p. 73).

Waller (2007) further speculates that various complexes of limbic attractors—each with correlated beliefs, biases, attachments and aversions—eventually form sub-personalities (p. 140). The limbic system identity, therefore, is viewed as virtually enfolding itself around one’s deepest nature, obfuscating it (p. 140). And because the developmental groundwork for thought and emotion have been laid in early development, the continued animation of thoughts and emotions—generated through unconscious energetic processes within existing neural networks—gives rise to the conditioned mind (Sadleir, 2009, March 10).

The Neurological Origins of the Personal Unconscious

Based on findings in attachment psychology (Hofer, 1983; Scheflen, 1990) and interpersonal neurobiology (Tomasello, 1993; Trevarthen, 1993), Schore (2003b), postulates that, in early development, the parent’s brain acts as a complementary brain through which the infant brain downloads important survival programs (p. 13). As this downloading continues, the infant brain resonantly connects with the parent’s brain, thereby gaining the available circuitry by which it can organize toward greater levels of complexity (p. 41). The forming personality, therefore, is largely the product of this interpersonal downloading process (p. 3), though other genetic, environmental and interpersonal influences undoubtedly impact the forming personality as well..

Godwin (2004) theorizes that, because the right brain is predominant during this crucial process, left modes of operation are unavailable for labeling disturbing emotional experiences (p. 112), so that the energy patterns of such experiences are unconsciously stored in the extensive circuitry already developed between the right hemisphere and the limbic system, making this system the neural correlate of the personal unconscious (p. 112). This theory might explain why the unconscious, in Jung’s psychology, is so often associated with imagery (also associated with right hemispheric function) and limbic-mediated affect (Miller, 2004, p. 25). The discovery that negative effect is most associated with right hemispheric activity (Davidson, 1992) may possibly be explained as the result of this right-originating personal unconscious.

References

Davidson, R. (1992). Anterior cerebral asymmetry and the nature of emotion. Brain and Cognition, 20, 125-151.

Geschwind, N., & Galaburda, A. M. (1987). Cerebral Lateralization: biological mechanisms, associations and pathology. MIT press: Cambridge, MA

Godwin, R. (2004). One Cosmos under God: The Unification of Matter, Life, Mind and Spirit. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional Intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. New York: Bantam.

Goswami, A. (2006). The Visionary Window: A Quantum Physicist’s Guide to Enlightenment. Wheaton, IL: Quest Books.

Hofer, M. A. (1983). On the relationship between attachment and separation processes in infancy. In R. Plutchik and H. Kellerman (Eds), Emotion: Theory, Research and Experience, 2, (pp. 199-219). New York: Academic Press.

Jiang, Y., & He, S. (2006). Cortical responses to invisible faces: Dissociating subsystems for facial-information processing. Current Biology, 16, 2023-2029.

Joseph, R. (1982). The Neuropsychology of Development. Hemispheric Laterality, Limbic Language, the Origin of Thought. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 4-33.

Krishna, G. (1997). Kundalini: The Evolutionary Energy in Man. Boston: Shambhala.

Miller, J. C. (2004). The Transcendent Function: Jung’s Model of Psychological Growth through Dialogue with the Unconscious. New York: StateUniversity of New York Press.

Mundkur, M. (2005). Neuroplasticity in Children. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 72(10), 555-557.

Muktananda, S. (1978). Play of Consciousness. Oakland, CA: S.Y.D.A. Foundation.

Sadleir, S. S. (2009, March 10). Recorded talk [MP3 recording]. The Self Realization Course: Precept 3, Self Awareness Institute Archives, Laguna Beach, CA.

Sadleir, S. S. (2003). The Self Realization Course. Laguna Beach, CA: Self Awareness Institute.

Sarnot, H. B., & Menkes, J. H. (2000). Neuroembrylogy, Genetic Programming and Malformations of the Nervous System. In J. H. Menkes, H. B. Sarnot & B. L. Maria (Eds). Child Neurology. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Scheflen, A. E. (1990). Levels of Schizophrenia. New York: Bruner/Mazel.

Schore, A. (1994). Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Schore, A. (2003). Affect Regulation and the Repair of the Self. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Tomasello, M. (1993). On the interpersonal origins of self-concept. In U. Neisser (Ed), The perceived self: Ecological and interpersonal sources of self-knowledge. Emory symposia in cognition, 5 (pp. 174–184). New York: CambridgeUniversity Press.

Trevarthen, C. (1993). The self born in intersubjectivity: An infant communicating. In U. Neisser (Ed.), The Perceived Self: Ecological and Interpersonal Sources of Self-Knowledge, (pp. 121–173). New York: CambridgeUniversity Press.

Tucker, D. M. (1981). Lateral brain function, emotion, and conceptualization. Psychol Bull, 89(1), 19-46.

Tucker, D. M. (1992). Developing emotions and cortical networks. In M. Gunnar & C. Nelson (Eds.), Minnesota Symposium on Child Development: Developmental Neuroscience (pp. 75-127). News York: Oxford.

Vaish, A., Grossmann, T., & Woodward, A. (2008). Not all emotions are created equal: The negativity bias in social-emotional development. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 383-403.

Waller, M. (2007). Awakening: Exposing the Voice of the Mosaic Mind. Livermore, CA: WingSpan.

Yang, E., Zald, D., & Blake, R. (2007). Fearful expressions gain preferential access to awareness during continuous flash suppression. Emotion, 7, 882-886.

- iAwake

A blog of consciousness studies, neuroscience, spirituality and the mind.